As more computer languages adopt functional constructs it seems pure functional languages have been pushed into a corner. Many developers are familar with closures in Javascript, and they are now available in Java, C++, etc., but pure functional languages are a bit different - they are stricter in the definition of “functional”. If functional is good, why aren’t pure functional languages like Haskell, OCaml, etc. used more widely?

Some developers claim pure functional languages aren’t practical, i.e. they are too strict and they don’t reflect the “real” (reality) world of computers because real computers have mutable state, and so trying to program without mutable state is just a mathematical exercise (and also hard for software developers). What’s reality got to do with programming languages?

Why choose between an pure or impure functional language? And are there really only 2 choices? Either we reject mutability and program in a pure functional language, or we just accept mutable reality and join the impure crowd?

I’ve thought about this question since I started using Elixir (5 years now), when trying to build a mental framework for categorizing languages.

Pure Functional Languages

“Testing can show the presence of bugs but not their absence” - Dijkstra.

In the early days of computer science, a lot of work was done to try to use math to prove program correctness. Think about that - it would mean that when you delivered your program to a customer you could say “this is provably correct so there cannot be any bugs by definition”, unlike today when we say “it has 80% test coverage and worked when I tried it” ;)

There’s no exact definition of fuctionally pure purity, but generally it’s these things:

- Immutable state / data,

- No side-effects

- First class functions (functions can treated as data)

- etc.

Javascript is a functional language. Why isn’t it a pure functional language?

- Javascript fails purity because it allows for mutation of state and side effects - most mainstream language fail for this same reason: Java, Go, C#, Rust, Python, Ruby, etc.

- Rust fails pureity because it has unsafe modes and allow side effects

- Erlang and Elixir fail this test because they allow side effects

What is immutable data and what is a side effect?

Functional Constructs

Mutation

I put 99 beers on the shelf. The shelf now has 99 beers. Hence, the real world has state. I take one down, and drink it, and now the shelf has 98 beers (and so on). The shelf has state has changed from 99 to 98 beers, i.e. mutated. The shelf is like a memory location in a computer and the count of beers is the value stored there.

Pure functional languages don’t allow mutation. In our beer analogy, the shelf with 99 beers can never be anything else. If you want a shelf with 98 beers, you’ll need a new shelf because the shelf with 99 beers cannot changed (i.e. mutate). Sounds wasteful! In pure functional languages beers don’t just disappear - there’s a reason (very useful!).

Does the real world have mutable state? Certainly seems like the mutable state matches our view of the world better and I can’t argue with that – this is the “pure functional programming is a lie”…

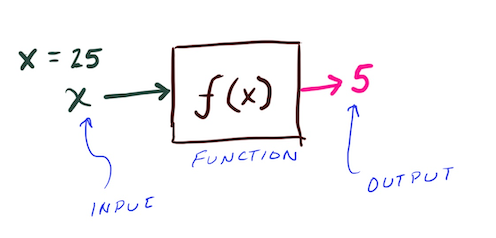

Diagram

Making this discussion as simple as I can:

- A function takes inputs and computes an output

In this drawing, x had an assigned value of 25 and after calling f(x) the output was 5. Possibly this function computes the square root, but we can’t know because it’s a black box.

- Pure functional language: x being 25 will always give 5 as an output. (in fact the whole thing can be substituted for the output, i.e. no side-effects)

- Impure functional language with side effects: x being 25, sometimes the output might be 5 and maybe other times it comes out as 3.1415.

- Impure functional language with mutation: sometimes 25 comes out 5 or 3.1415 and sometimes x might somewhat magically change to some new value like 52.

Of these three cases, mutation is the hardest one to understand and compose because the black box can no longer be treated as a black box - it can affect the world outside the box (the magical change of x). We must look inside the black box to understand what it did to x (or to see if it might change x).

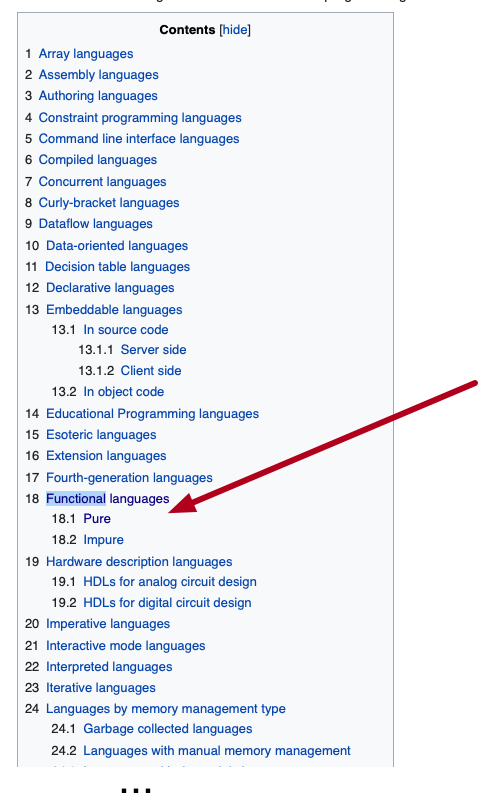

Programming Language Classifications

Take a look at this list:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_programming_languages_by_type#Pure

The list of functional languages has only two categories: Pure and Impure.

The list of “Functional Languages”, or languages that have functional constructs is very long nowadays! However, the list of pure functional languages is a lot shorter, e.g. Haskell, Ocaml, etc.

Where is the category: Languages with immutable data? Is mutation/immutable just a minor detail? ! ? I even tried searching Stack Overflow - “Computer Languages with Only Immutability”. Seems most developers answers misunderstood the question, or fail to believe it is possible to understand that there even is such a category.

There are at least a couple of widely used languages that have immutability only. The key word here is the word “only”, which means “there is no unsafe mode, there is only immutable”.

- Haskell

- Erlang / Elixir

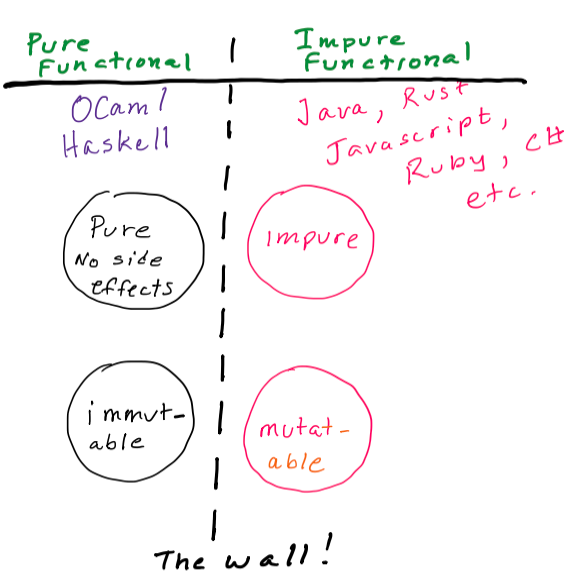

Here’s some drawings I made that focuses on only Pure and Impure as defined by 1) Purity (no side effects), and 2) Mutable (or immutable) data:

Pure and Impure

This is the categorization on Wikipedia:

- “Pure” = No side effects, and

- “Impure” = side effects

Here’s a diagram:

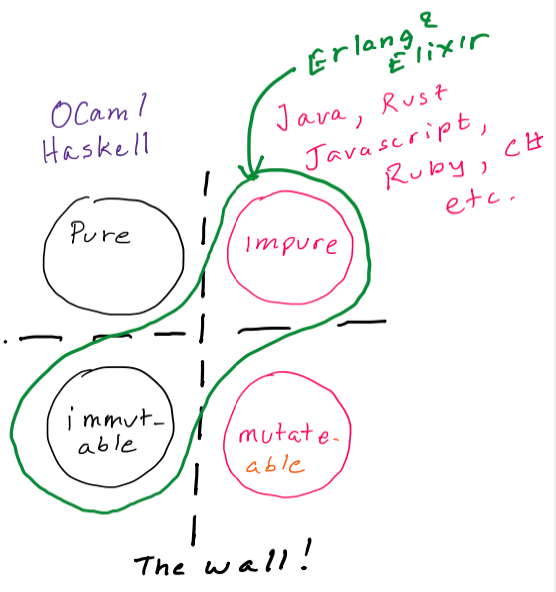

But where is Erlang and Elixir in this drawing???

Elixir and Erlang are impure, yet they do have immutable (only) data. You get an interesting cross category here:

Erlang and Elixir: Impure, yet Immutable.

Here’s what the list of functional languages should look like:

- Pure functional languages: immutable data and no side-effects

- Impure functional languages with immutable data: allow side effects

- Functional languages: allow side-effects and mutation

But “Mutation is a reality, the correct approach is disciplined mutation”

I can hear a thousand developer’s voices calling out that: Yes, but Rust, Clojure, etc., have immutable data constructs and that if you just keep your mutations under control and in a box then you’re ok.

Reflected by this statement: “Mutation is a reality, the correct approach is disciplined mutation. “https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=18044656

Maybe this discussion is for another blog, but the reason unsafe modes and mutation exists in these languages is because developers use them - and often use them incorrectly - there are studies that show vulnerabilities due to memory violations are not that uncommon: https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~yiying/RustStudy-PLDI20.pdf

Language designers often try to solve all problems with a single language. The justification for having mutability is often for performance reasons, but the performance gained by using mutation is dimished when you consider highly parallel and concurrent systems (which is pretty much everything nowadays). https://tomjoro.github.io/2017-01-31-world-changed/

Erlang and Elixir have a different answer: If you need mutation, then use some other language. This doesn’t mean you can’t use Elixir, it just means the unsafe parts need to be in other languages.

The Real World

Immutability - certainly Computer Science (everything is expressible with recursion) and math have it as a central concept, but what about the real world of computers?

Are computers just state machines that represent computation through global state changes? https://www.quora.com/Is-there-anything-you-don-t-like-about-Functional-Programming/answer/Jussi-Raunio?ch=10&share=4a170b91&srid=lM1b

It seems real computers have

- Mutable memory

- Global state

If working with functional programming and immutable data is so un-natural then why bother?

I thought about this, until I realized that an important piece is missing from the world view: time. Time makes the world immutable and global state impossible.

Time

We forgot to consider time in our world view - and time does exist!

The real world is actually immutable.

The real world is immutable when viewed at any point in time

- the past can’t be changed

- state is only definable by observation (at a time)

State arises from recursion in time.

There is nothing strange about defining state this way, in fact most computer memories work exactly this way: you can see this recursion at the level of the logic circuits that implement computer memory

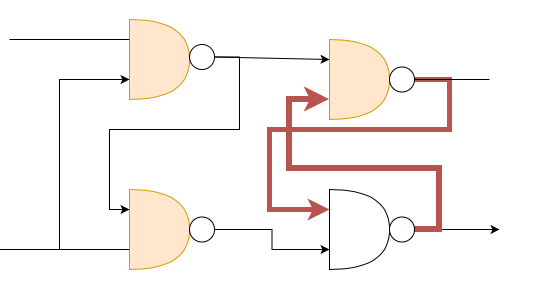

Here’s a logic diagram of a flip-flop. A flip flop is a 1 bit computer memory and is how RAM is built in a real computer.

You don’t have to understand this diagram, but notice how the lines feedback on themselves. Once you set the state on one of the lines, it recurses holding that state until the state until it is changed. And original computer memories were things like mercury delay lines, even CRTs, as recursed and repeatedly played back a signal put into them. In the past this was more apparent, but now this recursion is hidden in logic circuits.

The fact that time is real has further implications.

Global State

Time is real, and so it also prevents us from knowing the state of the entire world at any point in time.

Computers are connected to networks, have multiple cores, caches, I/O, GPU, etc. so how can global state exist? It can’t, because the world is distributed. This is especially true nowadays as computing has become increasingly distributed and parallel even on a small scale. https://tomjoro.github.io/2017-01-31-world-changed/

What does this picture look like:

So, even though each world internally uses immutable state, if viewed from the outside, i.e. observed, then it has state. BTW this is also where side-effects come from: things change somewhere else and we just have to accept that.

Elixir

Elixir: immutable data, and non-global state.

This is one of things that confuses people about Elixir - it seems there is state everywhere, but at the same time data is immutable!

In the Erlang/Elixir these independent “worlds” that each have their own local and immutable state are processes. Processes are single threads of execution that have observable state. State can be seen by sending a message to the process and asking it, and then the process sending you a response. Each process is a consistent world unto itself and has nothing shared with other processes. There are no mutexes, etc., in Elixir because there are no threads that can share memory.

This also matches the real world - state must be communicated to be known.

Process and the share-nothing approach has great benefits:

- Fail without interfering with other processes

- Cleanly terminated (from the outside)

- Take care of their own garbage

- etc.

In Elixir, individual processes can fail, self-destruct, or be killed, but the system as a whole can continue to run in safely (guaranteed).

Processes also make programming easier and code simpler, but that’s another blog: https://tomjoro.github.io/2021-12-30-elixir-doesnt-look-very-functional/

Is Pure Functional Programming a Lie?

Back to the original question: Is pure functional programming a lie? It’s not a lie, but it doesn’t always map well to the real world of computers - but not because of immutability, but from not taking time into the equation.

Elixir’s Category

One reason that it’s hard to describe Elixir to new Elixir developers is that there’s no “category” to refer to: is it “impure functional with distributed and immutable state” or “functional, dynamic, safe language” - it’s a lot more than just an impure functional language.

There is a middle ground between pure-functional languages and impure functional languages, and that middle ground is a category that Elixir defines. Elixir might not be a “solve all problems” language, but it does work efficiently in more situations that many developers thought possible. This creates a situation that drives the continued growth and adoption of Elixir.

And there’s nothing un-natural about it.

Disclaimer

Haskell is useful, Go is nice, I love Ruby, C++ is efficient, C# is handy, Java is solid, Rust makes sense, etc. - I’ve been programming for over 40 years and it’s not my intention to bash on other languages - comparisons that evoke emotions promote thinking and discussion :) and so happy coding!

(c) 2021 Thomas O’Rourke